kickstarting agile product development

Agile is all fun and games once you’re up and running, but how does one start developing a software product in an agile way? There is a lot of information out there about how to run an agile team - Be it with scrum, kanban, or any other flavor of a variety of agile processes. But when it comes to how to get started, most advice is “just get going”. So how does this “just get going” look like?

While it is tempting to just start hacking away, it helps to understand the basic premises, constraints, and the ultimate goal of a product. This is especially important if the software to be developed is not an internal product but is developed for someone else because we might not yet be intimately familiar with the business domain of a customer.

I like spending the first few days of any project to create an understanding of the context and the goal of the product. I aim to give the involved people enough information to foster autonomy and alignment about what we are to do. This does not mean to just gather more or finer requirements, but getting an understanding of “what the product will be about”. By formulating a product vision, an overview over the affected stakeholders and prioritizing the desired quality goals the context is usually quite well defined.

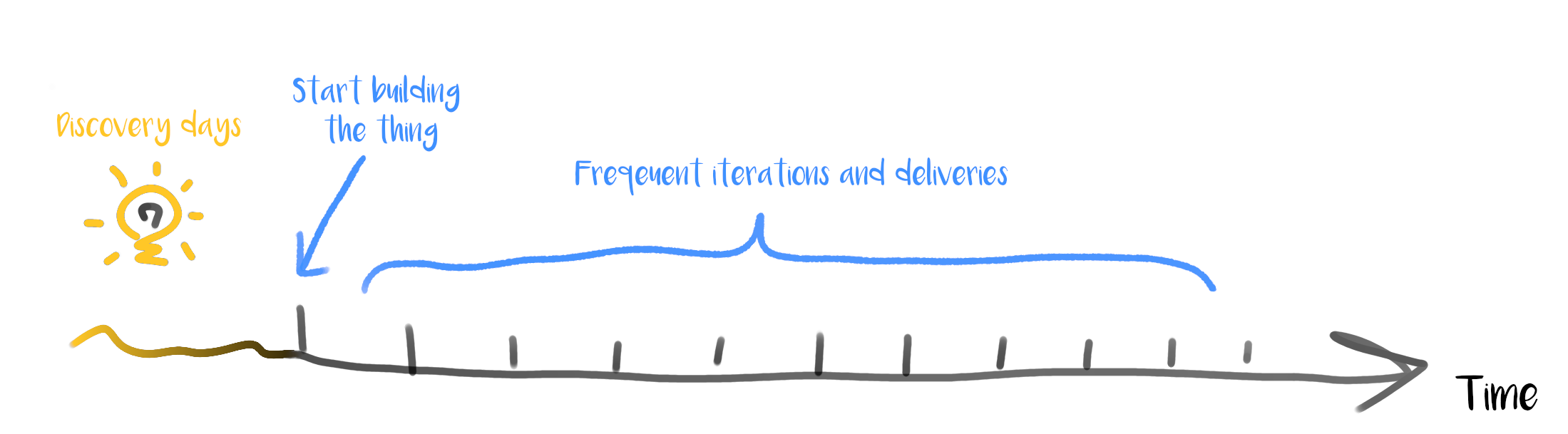

With the understanding of this context, creating a first story map and then distill a very minimal walking skeleton out of it often is quite straightforward. However, I like to stress that this “discovery phase” should be kept short, be confident to leave out a few gaps to be filled later - The sooner we start building the product the sooner we will be able to get real-life feedback.

Project vision - why is this worth developing?

Start by building the context by understanding the vision behind the product. This includes not just what we want to develop, but more importantly, why do we want to create that thing. Finding out what the driving force behind a product is, helps a lot later when the backlog needs prioritization. At this point, I usually just let my customers talk and then drill down into their ideas using the five whys technique - all while taking a copious amount of notes.

Often I try to switch the view from the product provider to the product user and ask “why would I want to use that product?” instead of “Why are we building that product” to get a more concise answer to the “why?”. Mostly I get the needed vision by just talking and asking, but if the vision turns out to be too fuzzy, investing the time to create a value proposition canvas is usually well invested. And yes, it happened that to me that a project was canceled at that point because we found out that nobody really knew why we wanted to build that particular piece of software.

Stakeholder map - Who is involved?

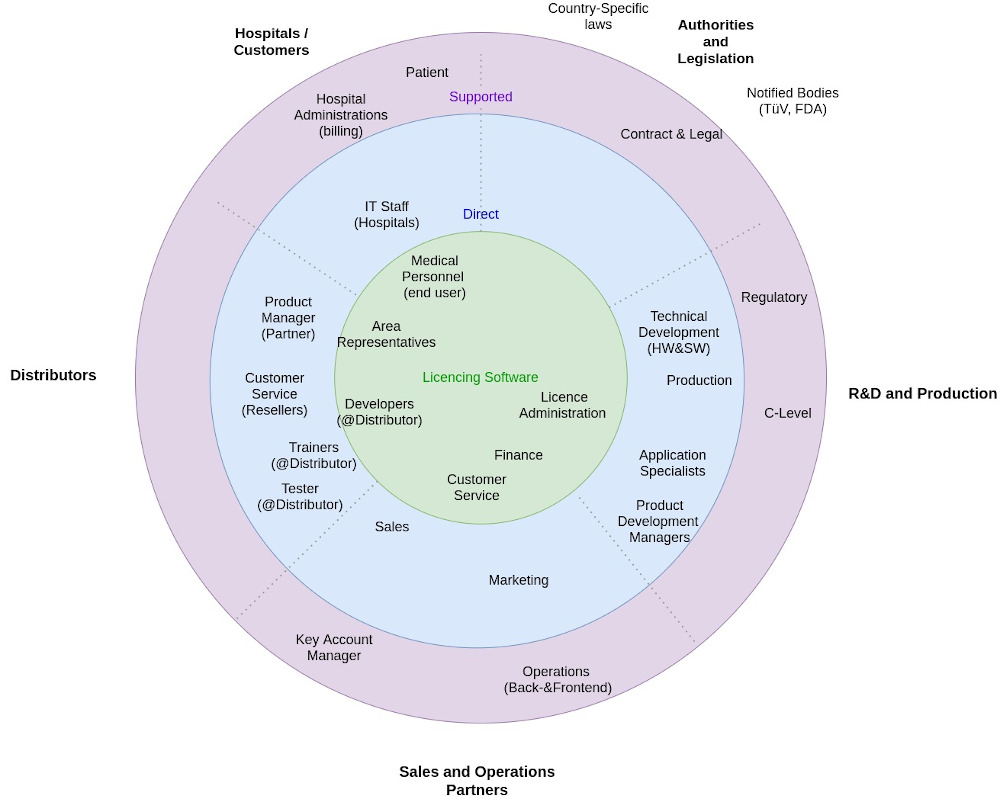

Once we have a rough idea of where we want to go with the product let’s have a look at who benefits from it. A frequent mistake is to group all stakeholders as “our users” or “our customers”. The stakeholders of a product are often a far more heterogeneous and diverse group than initially assumed. My tool of choice is to create a stakeholder map where the core users are at the center and the farther out the less direct the interaction and interest in the product is. Splitting them up along the organizational boundaries helps me to identify where their “allegiances” regarding the product lies.

Explicitly identifying the impact the product has on the different stakeholder groups is a first step to ensure we will be able to satisfy the various expectations. A good rule of thumb is to prioritize anything first that concerns the stakeholders at the center of the map.

Quality metrics - What does good mean?

By now we know what we want to do and for who we do it, so the next step is to figure out what makes the product good. For this I like to collect the quality attributes that the product will satisfy and prioritize them against each other. Coming from the med-tech industry starting from the iso25000 quality attributes is kind of natural for me. Maybe I add a few further attributes like scalability or patient safety to the list, but I keep the number of quality attributes small and easily manageable.

While I consider a full-blown QFD analysis an overkill at that stage, creating a QFD-like matrix of pitching the requirements against the prioritized quality attributes is a great enabler for early and fast decisions regarding the software architecture. And again having the quality attributes ranked might give a hint on what to do first in the walking skeleton.

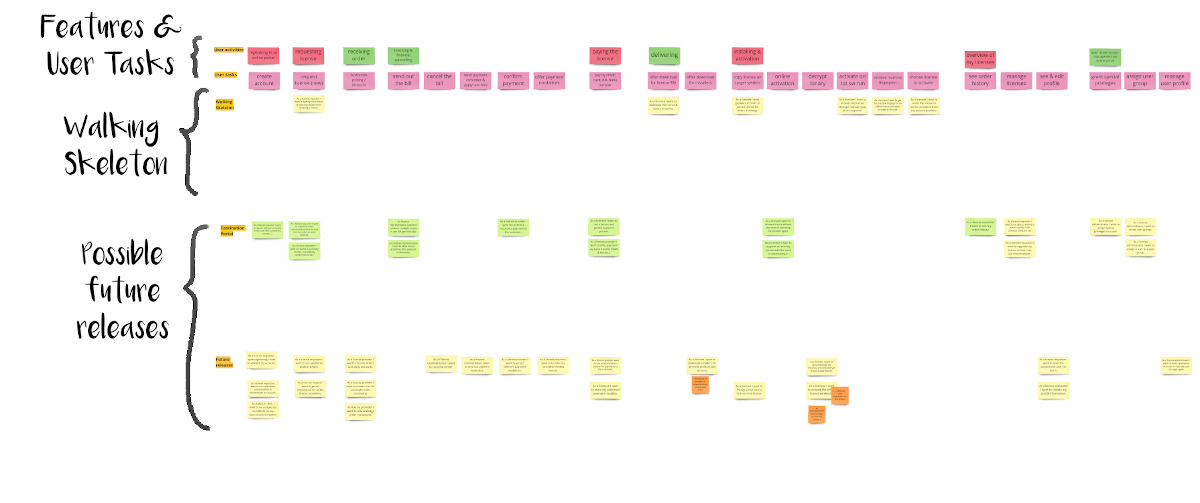

Story mapping - building a narrative

Finally, we’re talking stories and start building a lean backlog. My method of choice to create a backlog is story mapping. The goal of the story map is to create a narrative of the desired features and bring them into context with each other. First I want to be able to tell the high-level narrative, and only then do I start refining the stories. Be rigorous with prioritizing here, anything not strictly necessary gets chucked out or deferred to later. Since we’re at the beginning of development the user stories are still very coarse and might lack acceptance criteria. This is fully intentional, slicing them and creating the full lean backlog will come later.

Double-check the stakeholder map against the story map frequently. If some of the core stakeholders are not found on the story map, chances are that a vital part of the product is missing or that our stakeholder analysis is off.

Defining a walking skeleton - One vertical spike

Almost there! The narrative for the product is set, so let’s go lean! Lean and agile development means getting early and frequent feedback. Our first goal is to define the minimal set of features needed to determine if the base use case of the product is viable or not. As a rule of thumb, anything that either concerns stakeholders not in the core circle or that concerns special cases gets deferred to later for now. Ask for any story: “can we start with a workaround at the beginning?” For instance, instead of automatically processing the billing for an e-shop as “can we handle it manually over email for the first 100 customers?”

It pays out to be radical here and trim the walking skeleton down to the absolute minimum. No fancy extra work, no edge cases unless they are legally required. For most products that I worked on the walking skeleton could be defined in less than ten stories. Of course, they will get split later, but if the core use case cannot be explained in ten sentences or less, chances are that the walking skeleton is still too complicated.

… And off we go

At that point, development can begin in earnest. Refine and slice the first story to a usable size and start coding, build the architecture, and set up the CI/CD environment. Setting the context from product vision to story map typically takes a few days at most and the first story or spike should be ready within days or at most a few weeks to get early feedback. Bear in mind that the story map is a living document and will change frequently. Compare the narrative with what you learned since the last iteration and adapt. The stakeholder map, vision, and quality criteria tend to have a longer lifespan but nevertheless take them up frequently. Make these documents visible in your daily stand-ups and do over them in detail whenever you talk about the longer future like when building an agile road-map.