The joy of failure

“We only learn through failure. This quote attributed to the legendary alpinist Reinhold Messner holds a lot of truth in it. Modern organizations like to talk about good failure culture, but is a failure in every circumstance a good thing? Probably not. As a software engineer and climber, I saw a few failures with sometimes quite drastic consequences. Failure is never the goal but sometimes unavoidable, so how can we as individuals, teams, and companies benefit from it?

When climbing, failure is usually much more apparent and immediate than when working as a software developer or other office job. If a summit is not reached or one falls a few times during sports climbing one feels the failure. In software engineering failure is usually more abstract but nevertheless very present. Mistakes can have dire consequences as well, just think of defective software for an airplane.

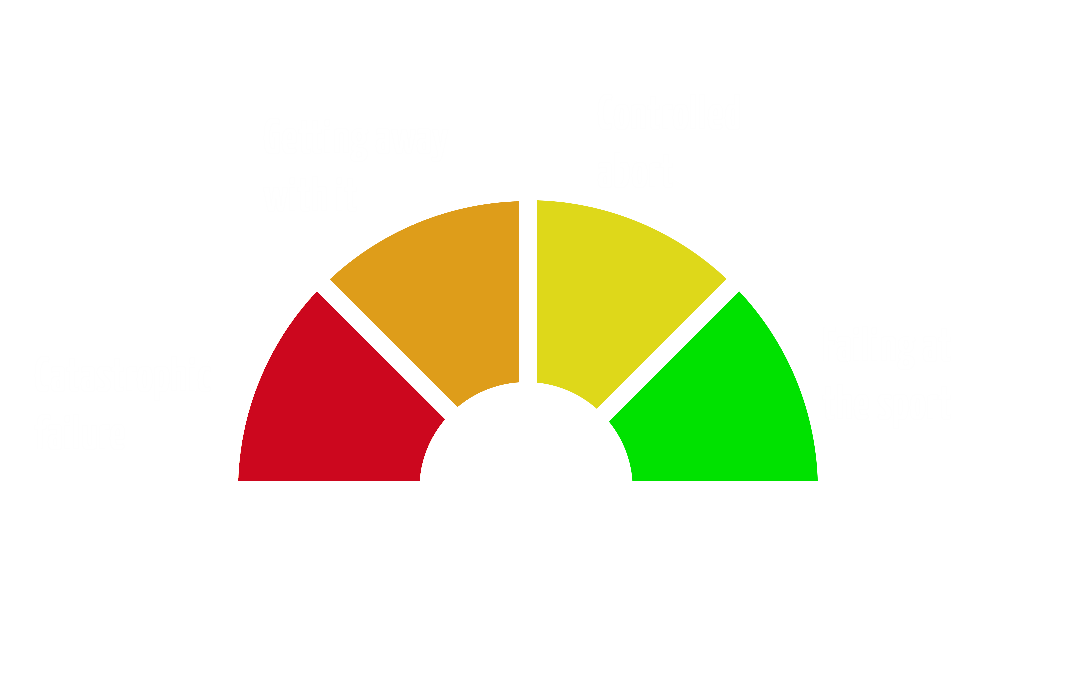

But is every mistake important and a valuable lesson? Where can we embrace failure and where do we have zero tolerance? Years of climbing and software engineering made me categorize failures into four categories.

Failing at the sport

At the inconsequential end is what I call “Failing at the sport”. Failing here is usually related to the way we would like to do things. The intended goal might still be reached, but not in the way intended. One stands at the summit, but the ascent was not a “red point”1 ascent. In software engineering, the feature is still delivered, but we failed to do so by applying TDD or using a certain technology.

This kind of failure happens very very frequently, and while we want to be aware of it and learn from it, this should not slow us down in our daily work. Acknowledge the failure, think what could have gone better, train and learn a bit and move on to the next software feature or the next big rock to climb.

Controlled abort

The next level is what I call “controlled abort”. The goal is no longer achievable and that fact is recognized early enough for a controlled rollback. We are still in control of the situation and it is a conscious decision not to press forward. Maybe the climb is just too difficult and the summit is unattainable, so rappelling down becomes the only safe option left. Or the team recognizes that a software feature does not bring any value or might lead to a technical dead-end. Whatever the cause, pressing on will not make much sense. Here a conscious decision happens to stop because else the consequences will be nasty.

Failing this way is often very frustrating, but it also avoids damage or injury. It takes some experience and will to decide to turn around and abandon the already-done effort. A thing that is never easy.

Getting away with it

If we fail to recognize the exit point for a controlled abort the situation becomes dangerous. Suddenly the situation on the mountain is out of control and the possibility of broken bones or even death becomes very real. A critical security bug just showed up in production or the last bolt popped out of the rock. When this happens our goal dramatically shifts from “reaching the goal” to “containing the damage”.

Reaching the original goals is now very unlikely and the consequences of failure might become quite severe. These are the situations where one often asks afterward, “How did we end up there?”. In this zone, one needs all his experience, skill, and some luck to avoid severe damage, be it financial damage or suffering reputation, or in the case of climbing severe injury. I call this zone where one momentarily went too far, the “Getting away with it”-zone.

Catastrophic failure

Pressing further on will lead to “catastrophic failure” and possibly a headline in the newspapers. The question here is no longer if someone gets hurt, but only how severe the damage is. Any further work on such a project will only lead to more costs or an even more dangerous situation. Surviving - literally and figuratively - such a situation will make one think twice if one still wants to pursue a career in software engineering or keep climbing. Under no circumstances do we want to end up here. No matter what our failure culture is, these kinds of failures are so damaging that they have to be avoided, almost at all costs. In this area, it is much better to learn from other people - those who by some miracle or sheer will manage to survive a catastrophic failure.

These are the software bugs that caused failures in pacemakers, that faked the measured emission at Volkswagen, or that caused the recent crashes of Boeing 737s. Or the many climbers that pushed despite bad weather or lack of skill until someone got hurt. It does not matter if one finds himself in this situation because of one’s own fault or from external circumstances - the consequences are the same.

Getting control back

The boundaries between the types of failure are fuzzy and depend on the skill, experience, and personality of each individual. An experienced climber might still be in the green zone while an absolute newbie is already overwhelmed in the climbing gym. Especially the transition from “Controlled Abort” to “Getting away with it” is very hard to anticipate. Suddenly we find ourselves in a situation that we can no longer fully control.

What happens here is very interesting. After the initial reflex of Fight, Flight, or Freeze is overcome, absolute concentration sets in. Software and mountain climbing both require systematic actions to solve problems not hectic actionism. Once we are in such a situation all the knowledge and skills are activated to get the control back. The software is reverted to a stable version, a patch is provided or we inch back to a safer spot with an improvised pulley system. Step by step the situation is resolved until the situation is getting closer to normal or routine.

Once back in the zone of “controlled abort”, actually aborting and getting back to safety is highly advisable. Suppressing the impulse to still try to reach the summit or push the feature through nevertheless will save lives.

Open, brutally honest communication in a team or rope party is indispensable in this situation. Not just in a situation of immediate danger, but until one is back on solid ground. Reflecting and learning from the just experience becomes key to further success.

The joy of failure

The crisis has been averted, the damage was acceptable to its extent, and there the “itch” to succeed returns. One wants to go back up that mountain or deliver that feature that caused so much headache.

With a beating heart, we stand back at the foot of the wall, or we take the story from the scrum board. Taking a deep breath we tie in and look for the line of code to dive into the program. The journey starts slowly and with utmost care at first, until we reach the point where things went bad last time. And there it is. That tight spot from the last attempt. We nod to the climbing partner and ask a buddy for pair-programming and off we go. Line for line, move for move the problem is formulated and protected with nuts, cams, and unit-tests.

Higher and higher we climb and finally we send the feature into the CI-environment. All tests pass, a last heave and we stand on top. Enjoying the marvelous view and admiring the users using and enjoying the delivered software is an amazing feeling!

Full of pride we look back at how we went through hell to get here. How horrible and how good the experience of overcoming a near-catastrophic failure was. And we know that reaching this summit would not have been possible before. Knowing that experiencing these moments of dread and despair provided the necessary learning experience to finally reach the top is incredible. And this feeling, this moment, that is the joy of failure.

This article was inspired by the article “Staying alive” by John Dill of the Yosemite Search and Rescue

find the article in german on blog.bbv.ch

-

“red pointing” a climb means that the route was climbed without hanging into the rope. ↩